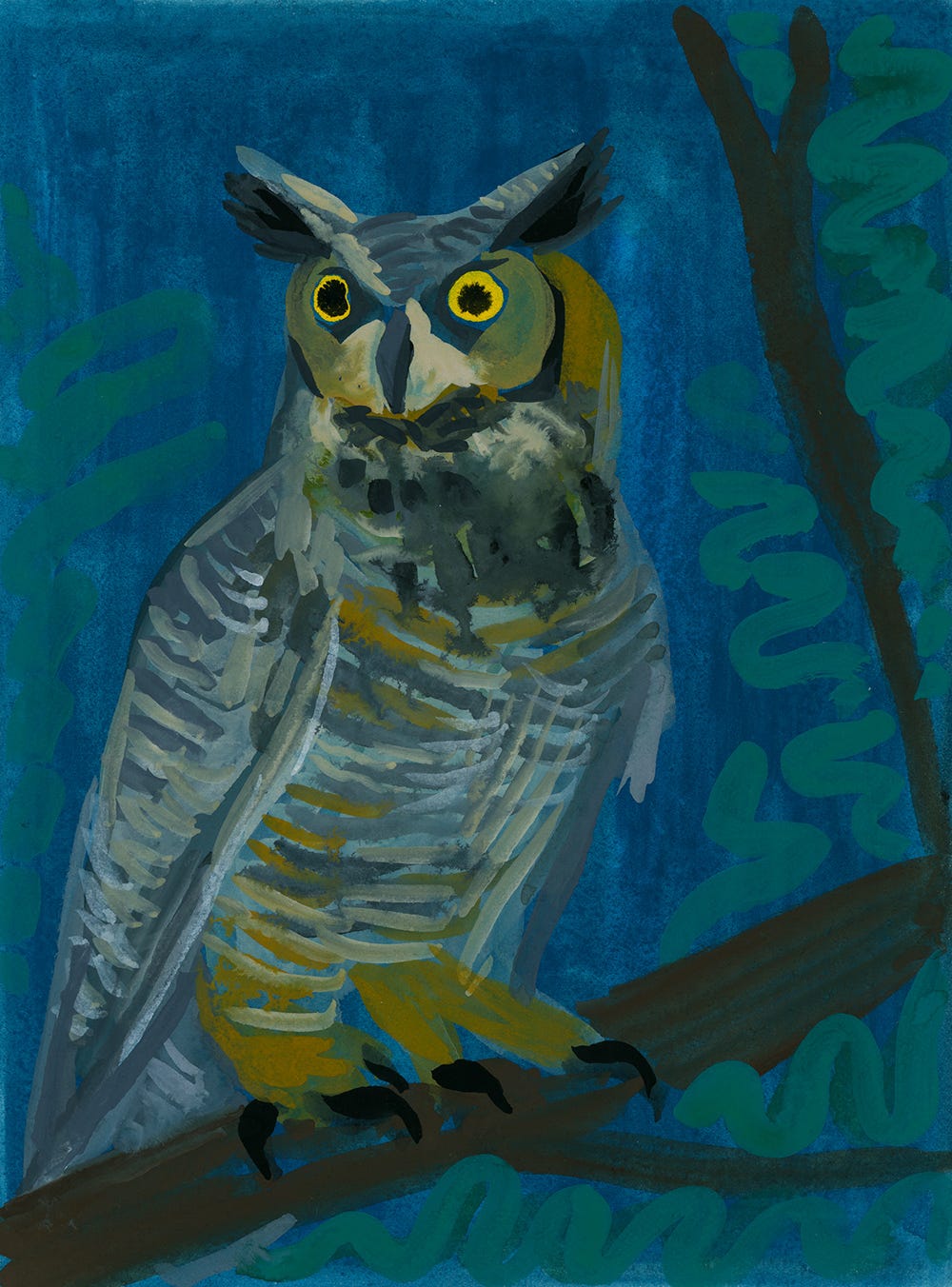

Hi, friends—this is issue #3 of my Friday newsletter about animal encounters. Please reply with any comments, suggestions, or stories. This week is the haunting and fierce great horned owl (Bubo virginianus). Thank you! Amy Jean

More often than not, if I awake in the middle of the night, I can hear the call of a great horned owl. She hoots a sad call: hoo hoo hoo hooooo. I’m never sure if she woke me, or if, somehow, my waking called her into existence. I find her comforting in the dark.

I know the owl’s calls are not for me, exactly, but then again her calls are for all living things. She perches in the red oak above our house. We are part of her domain.

Sometimes our crazy dog grumbles back at the owl. Years ago when we first brought our dog home from the pound, she would bark back at the owl, through the ceiling, out the walls, and into the night. The owl would pause and then hoot back. They seemed to be having a conversation: “I am here, in the wild.” “I am here, in a house.” Martina (our dog) has since grown accustomed to the owl and only grumbles.

At 3am, we three—the owl, the dog, and I—are awake and listening. I’m the only one who shouldn’t be here, now, at this hour.

I’ve seen the owl maybe once or twice, swooping through the trees at the end of the day. Great horned owls move through the air seemingly without touching it—there is no trace of disturbance, no quiver of sound. It is eerie, as if watching a silent movie in real time. Her wing feathers separate into soft fingers so that the air moves through them rather than around. She is a silent hunter, a shadow with sharp talons.

I’ve heard the owl more than I’ve seen her, and I like that my understanding is limited this way. Great horned owls live from 5 to 15 years, so it is possible (though unlikely) that it is one owl whom I’ve grown accustomed to hearing these past 12 years. Females have a higher pitched call than males—and at times I’ve heard him calling back in the distance. Mated pairs occupy the same territories year-round and will stay in a single territory throughout their adult lives (most mate for life, though males are not always monogamous). Their calls are a claim to this territory; the owls are communicating and defending it at once.

When I hear the owls at 3am I think of the nighttime animal network, of the life (and death) that happens while we sleep, and how animals take turns on the surface of the earth, folding into niches. The most common animals have adapted to changing circumstances, since folding into small niches has become increasingly more difficult.

The great horned owl shares ranges with the red-tailed hawk, who is in a sense its diurnal (daytime) equivalent. Great horned owls range comfortably across the continent. They prefer areas with open habitats, so it’s less likely you’ll see them in cities or suburbs (though not unheard of).

Great horned owls have giant saucer eyes, among the largest proportionally and highly adapted for night vision. They have the appearance of being able to see clear through you. Great horned owls have great hearing, too (ten times more sensitive than ours), and, like other nocturnal hunters, their ears are positioned asymmetrically in order to triangulate the origin of sounds. Curiously enough, the tufted bits have nothing to do with hearing and are something of a mystery (they might aid in camouflage, but no one knows for sure).

Great horned owls will eat just about anything that moves, with a focus on rodents and bunny rabbits (our dog is not wrong to be nervous). Owls can crush small creatures easily with their talons and pop them into their beaks whole. Larger creatures require more gruesome work. You may have heard of owl pellets—the regurgitated mass of undigestible bones—and sometimes whole tiny skulls can be recovered from these. It is an efficient system for a creature that needs lots of calories and doesn’t have time (or the mechanisms) to chew.

Great horned owls have no natural predators except for humans (and our infrastructure). Crows will gather to harass great horned owls endlessly, and we’ve witnessed this at times (our dog chases the crows, who also harass her). All of us are shifting into each other’s spaces and the limitations of our perception lock us into one knowable world. But that doesn’t mean that other perceptive worlds aren’t happening simultaneously.

The great horned owl’s sad low tones may indeed wake me from my sleep, pulling me from a dreamworld into another real world—her world—normally invisible to me. Her calls may not be for me, exactly, but they are for all living things, alerting us to her existence, her place in the trees, letting us know:

“I am here.”

Great horned owl links—

Try staring into an owl’s eyes for 20 seconds at the beginning of this video. Her gaze is truly intense.

There are many recordings of great horned owls calling to each other: I like this night cam in grayscale from Cornell Lab Bird Cams; Bird Note is always short and terrific; and you can get lost in the recordings of the Macaulay Library and never return. eBird brings everything together, here.

In other owl news, reporting from NYC: Barry the barred owl in Central Park; and everyone’s favorite tiny saw-whet owl in the Rockefeller Christmas tree.

Turkey and bear stories—

No one has any bear stories, yet, but there is a new turkey story with a truly bonkers number of turkeys—plus a bobcat, from Susan in Oregon.

Also—

Both owl drawings are for sale; please reply if you’re interested.

Next week: America’s only marsupial, the ghostly, misunderstood opossum

Please share this newsletter with friends who sent you news of the owl in the Rockefeller tree—thank you!

Thank you for your lovely, peaceful writing, and for spreading your appreciation of animals. I've copied below an owl story I just received from my mother's dear friend Sunny in Wisconsin. It instantly made me think of Wild Life, and I got permission to share:

---

So….a few summers ago, all the grandchildren were here playing all afternoon—riding scooters, playing croquet, playing in a blow up pool (small) etc. and three of them spent the night. In the morning, as I was making breakfast, and they were all out on the porch, one of them called to me, “Nonnie, something is caught in the soccer net in the lower yard. “

(Note to self: NEVER, EVER leave netting of any kind up overnight—badminton, soccer, hockey, whatever.) When I got to the bottom of the bluff I could see immediately that it was a very large great horned owl completely wrapped up, wings trapped, in the soccer netting. He was exhausted, and I was electrified. He had probably been flying down for a mouse or something, and flew into the netting, and got trapped. Then he struggled for hours, and so was unbelievably tied up.

I didn’t know anything about saving an owl like this—e.g. put a towel over his eyes so he’s not so scared—always wear heavy gloves as his claws could rip my hands and arms right open—etc. I just knew I had to act fast—told Rowan to go up to the house and get me my phone and some scissors. I figured if I couldn’t free him, we needed to call animal rescue to come and help. I called them anyway to tell them what was going on—but had to leave a message as I only reached an answering machine. Well, it WAS on a Sunday.

Anyway, I kept talking to the owl in my softest voice and gently began touching him a little so he wouldn’t be shocked when I began snipping at all the netting so I could free him. It was amazing—he looked right in my eyes the whole time, and never struggled even a little bit. Like the hawk, I’m sure he knew I was only there to help him. It seemed like I snipped for hours—but it was about 20 minutes, and I started with his feet. It was like he was in a netted cocoon. I had the kids stay a good 20 feet away, and they were totally quiet as I’d asked. When I reached the owl’s shoulders, there was just one piece left and I couldn’t tell if it was around his wing, or just resting there—and I hesitated because I would have to come SO close to his beak.

What happened next made me cry. He had been on his back this whole time—totally still. He suddenly flipped over and onto his feet. I was so worried that he was hurt and wouldn’t be able to fly. Then he turned his beautiful face towards me, the way they do, looked at me straight in the eyes for a long minute—lifted his wings and flew across the river to a tree. I’m telling you, we were beside ourselves. The children were whooping and shouting with happiness and delight—I was crying and unable to speak—I’ll never forget it. That’s the day he became my spirit animal. He is still around all the time, I’m convinced—as a few weeks after that, as we came out the front door, a huge owl lifted out of the tree right outside the house, and flew back to the river. And we hear him hooting most nights. Owls are territorial and as we know from Wesley the Owl, they also can connect to a human being.

Meanwhile, another time, I looked out and saw something odd moving along the grass in hopping movements, next to the river. I immediately thought ‘hurt owl’. I called Danielle as she is just like us, to see if she had a box big enough for the owl, as I knew I didn't. She arrived within minutes. By now I’d read all about how to help injured birds. Never put food or water near them, for instance, as it will bring other predators to them while they’re helpless. If the bird can’t fly, put it carefully into a large box and in the dark—like the garage—to give it time to rest and recover before letting it go. It turns out that none of that was needed, as this time, I think the owl had probably flown into a tree and hurt itself, but—as Danielle and I approached inch by inch, he moved to the stone bench next to the river, hopped up onto it—and after a few minutes flew up into the tree above it. Wild celebration and happiness ensued. :)

From Tom in Indianapolis:

We had a mom and two fuzzy chicks roost in our yard this spring. The crows would yell at them all day, then the chicks would call out every few minutes all night while their mom was hunting. All inside the city limits of Indianapolis.