Hi, friends — you may have noticed I skipped an extra week (ah, summer!), but I’ve had these little beetles, a favorite evening spectacle, in mind for a while. I prefer them to fireworks because of their quiet there/not-thereness. They illuminate and commemorate the tail end of daylight, as if any of us are ready to see the sun go. As always, please share your stories in the comments or you can always reply directly to this email. — Amy Jean

The other night I walked out the front door, around 8:30 pm, to relax for a minute in the hot-summer air. To my left, down our gravel driveway, I saw a bunny sitting in deep shadows, its puffy white tail acting as a small beacon. Soon it would disappear entirely into darkness.

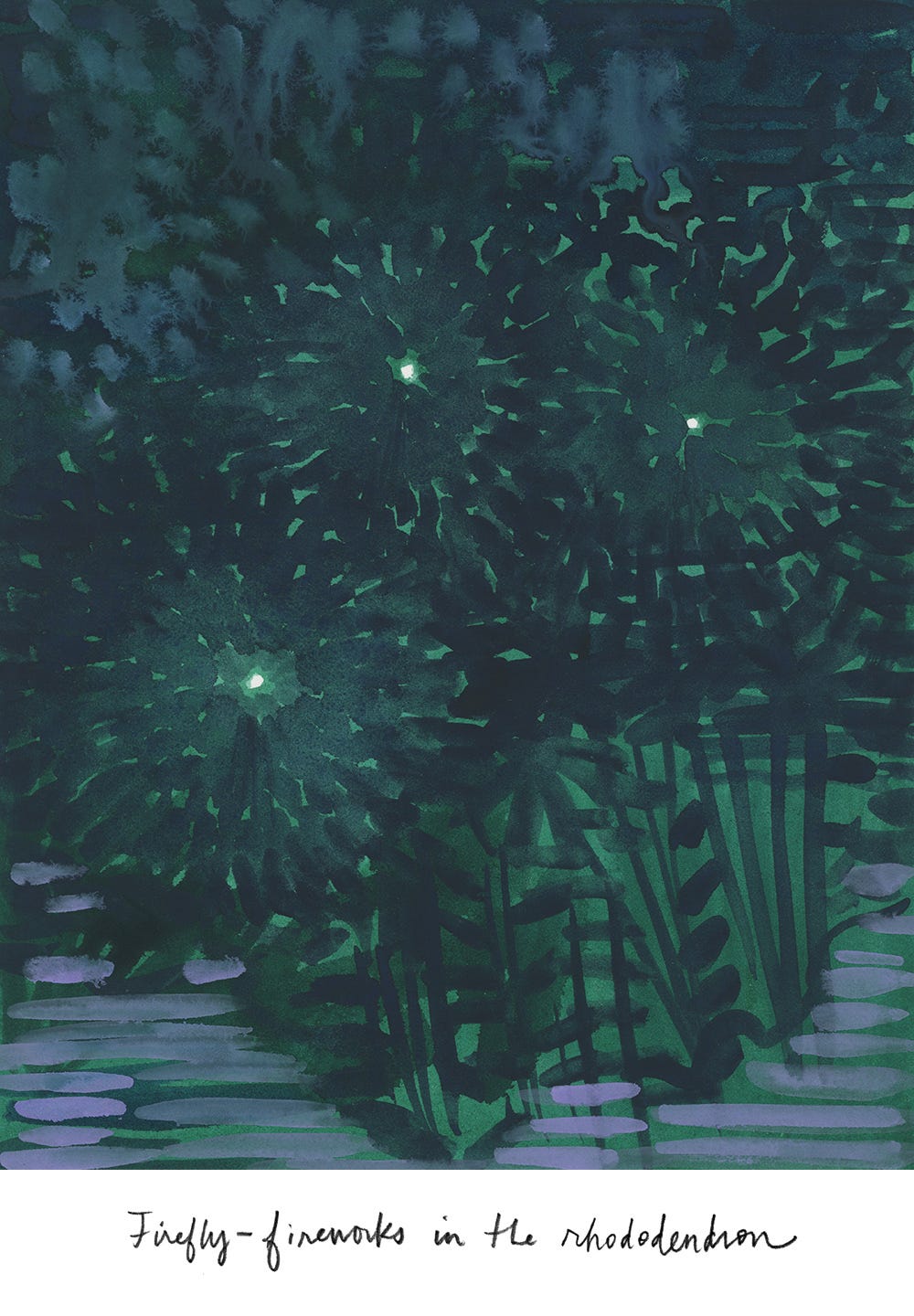

Above me I could feel the presence of two bats, like ripples in water, flitting quietly. A firefly blinked in the forest greens of the rhododendron, and then blinked again. It was a charming tableau, a reward for opening the door. I watched for a moment, this little show between day and night. The bats fluttered, the bunny bolted, the firefly blinked.

And then, I noticed a blinking red light on the dashboard of our car, parked alongside the rhododendron. The car blinked and then the firefly blinked. The car blinked and then the firefly blinked—blink, blink, blink. And then they blinked together, the firefly and the car.

When I was a kid in Oklahoma we used to chase fireflies, or lightning bugs as I knew them (and indeed there is more lightning in Oklahoma). I caught a lot of bugs in jars, adding leaves for comfort and punching air holes in Saran wrap covers. Watching their little abdomens glow is perhaps the nearest I’ll ever get to true magic.

The lantern action of fireflies is the result of a reaction between oxygen (the presence of which the fireflies somehow control) and a chemical that is poetically and aptly called luciferin (from the Latin word “lucifer,” meaning light-bearing). Firefly light is a form of bioluminescence, more common in deep-water creatures, but also some fungi (because fungi are wondrous). It is pure light with almost no heat.

Firefly light may have evolved as a warning to predators (they deal a toxic blow to any creature attempting to eat them), but it has adapted as a mating signal and mode of communication. There are 2,000 species of fireflies around the world (warm and temperate zones on all continents except Antartica) and their ranges overlap, so it helps to be able to identify your own species through its specific, blinking light.

Fireflies spend only a few short weeks as adults, and their goal is to reproduce (some species don’t even eat). They lay their eggs in the ground, under leaf litter, and little glowing larvae emerge in late summer. These creatures spend most of their lives in this larval stage, eating slugs and worms. In spring, they pupate and become the flickering, flying creatures we know so well.

The firefly by the rhododendron was most likely a common eastern firefly (Photinus pyralis), also known as a big dipper firefly because of the shape it makes while flying (but I also like this name in the context of constellations). Did the firefly think the car alarm was its true love? It wasn’t deceived for long, but I could feel a sense of disappointment and embarrassment hovering in the air.

I often feel this way when I think of the many creatures trapped in a human world. They find the spaces in between, they settle in the shadows; they do their best, flickering their small light, here and not-here.

Firefly links—

For the full science on firefly light, I found this article helpful [Scientific American]. I also like this list of luciferin types (foxfire is for fungi) on Wikipedia.

What happens when a frog eats a firefly? This is what happens when a frog eats a firefly. [it flickers—via YouTube]

Firefly or lightning bug? Here’s a handy map [via Mental Floss].

Scroll down for a few long-exposure photographs of fireflies and stars, the big and the small [via EarthSky].

Animal encounters in recent comments—

On the Wild Life summer diary, a really lovely story of barn owl parents teaching their fledglings about life in the pine trees, from Katherine—thank you!

Also many thanks to Susan for the sparrows in a chain-link fence and a sapsucker alarm clock, which seems like a great way to start the day.

Also—

Animals may be trapped in a human world, but sometimes humans are trapped in an animal world—I love this new memoir by my friend Chloe Shaw, What Is a Dog?

My firefly/fireworks drawing is for sale. Some of the proceeds will go to the Fireflyers International Network. Please let me know if you’re interested, or you can also take a look here.

Next time: a summer surprise, here comes August!

Wild Life #27 / this newsletter is a place to learn about the life around us, one small step/paw/tiny heartbeat at a time. If you enjoy reading, please share with a friend, neighbor, niece, nephew, cousin, sister, aunt. Have a great weekend and I’ll be back in a couple of weeks.

We have glow worms in New Zealand, but not fireflies to my knowledge, although I read American books as a child so I knew about them. This was really interesting and the glowing frog video was fascinating

Beautifully written. I was just reading about Dark Sky preserves and other efforts to reduce light pollution for the sake of wildlife; the connection you draw between constellations and fireflies really seems to bring that all together nicely.