Hi, friends — this is issue #15 of my newsletter about animal encounters. If you’re new, welcome! The barred owl (Strix varia) is a friend to many. Thanks for reading, and, as always, please add your stories to the comments, or you can reply directly to this email. Thanks! — AJP

We don’t have barred owls in our neighborhood, and I think it’s because we do have great horned owls, their eternal nemesis. But of every possible owl or even bird species, I’ve definitely heard the most stories about barred owls: one nesting in a friend’s backyard; one coming when called, like magic, out of the woods; one preening and hooting in Central Park; one visiting a back porch; one mistaking a hat for a squirrel—to name a few.

These small stories, sometimes told in passing, sometimes in longer conversations with friends, have brought me closer to understanding barred owls. There’s a different quality of knowledge that comes with first-hand, everyday stories, even if they’re only a sentence or two. The wonder and emotion at their core are central—and the stories stick (and really, that’s exactly what this newsletter is about).

Barred owls have a wild, Halloween-sounding hoot. Listen to their call here and perhaps you will hear “Who cooks for you? Who cooks for you all?” (I love how bird songs are “translated” into human language in often amusing ways, though admittedly this one is harder for me to wrap my ears around.)

The barred owl’s call is so distinctive and common within its range that abolitionist Harriet Tubman, who was a knowledgeable naturalist, used it to guide people escaping to freedom along the Underground Railroad. Her imitation of the owl’s calls communicated whether or not it was safe to move forward.

Barred owls are territorial, and fascinatingly sedentary. A mated pair will pick a spot and stick with it; one study found they did not stray beyond 6 miles over their entire lives. So, if you have barred owls near you, they’re reliable neighbors all year long, and potentially for decades. They don’t seem terribly bothered by people (hence the backyards and city parks), though they’re more likely to be heard than seen.

Barred owl pairs aggressively protect their territory, particularly when it’s nesting season. The clutch is usually two or three eggs, which the female keeps warm while the male hunts and provides for her. The chicks fledge in a few weeks but stay close to home for months, learning to hunt from their parents.

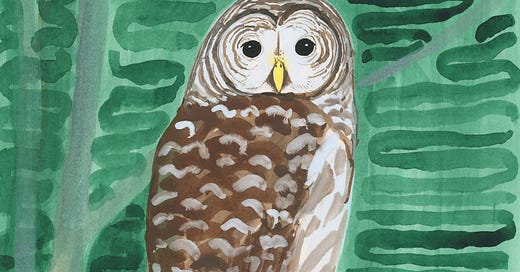

The name “barred” comes from the bird’s beautiful patterning. The dark bars running vertically on their chest offer a counterpoint to the softer horizontal bands running along their wings and back, punctuated by pale half moons. The patterning allows them to blend into the canopy as light flickers through the trees. It’s easier to spot them in winter, when their dark eyes make an impression against pale skies. Their range, once limited to eastern North America, has expanded west in recent years, complicating life for the more timid and endangered spotted owl but filling the air with “Who cooks for you?”

Someday, I hope I will hear the call of a barred owl and that I will remember this cooking lesson of theirs, and will also think about Harriet Tubman’s guidance and giving, and will remember the many stories from friends, too. In that quick burst of sound I will understand something more of a barred owl, living freely around us—a wild life brilliantly shared.

Barred owl links—

“Harriet Tubman, an Unsung Naturalist, Used Owl Calls as a Signal on the Underground Railroad” The famed conductor traveled at night, employing deep knowledge of the region’s environment and wildlife to communicate, navigate, and survive [Audubon]

Bird Note has a nice, short feature on barred owl calls that helped me hear “Who cooks for you?” plus their excellent maniacal-sounding calls [Audubon]

3 minutes of highlights from a nest cam last year: please wait to watch an owlet wink! [Cornell Lab]

Jason Polan, an artist I greatly admired, beloved by all, made drawings for the feature “Every Bird Has A Story,” including the barred owl [Audubon]

Animal encounters in recent comments—

So many mourning doves in our lives! Thank you for sending in your stories. Here’s a great photo for one, from Michelle, who managed to collect some of their iridescent feathers. I will never see a mourning dove again without thinking about this pink:

Also—

Next week: considering the fact that I’m watching one hang by its toes from the bird feeder right now, I think it’s time for me to consider the smart, hilarious gray squirrel.

My owl drawings are for sale; please reply if you’re interested. I’ll send some of the proceeds to the Owl Research Institute.

Thank you to Adrian for introducing me to Hinterland Who’s Who (honestly thank you to all Canadians for this brilliance). Here’s a short one from the 1970s about the common loon [YouTube].

Thanks for reading and please add your stories and share with friends. Let’s appreciate these creatures while we can. This newsletter is a small weekly adventure about the life around us.

A Barred Owl that has been my neighbor for YEARS landed on my balcony this week (my spouse's photo and IG) https://www.instagram.com/p/CLrhUYOBzxp/?igshid=1qiskmljqvwdx