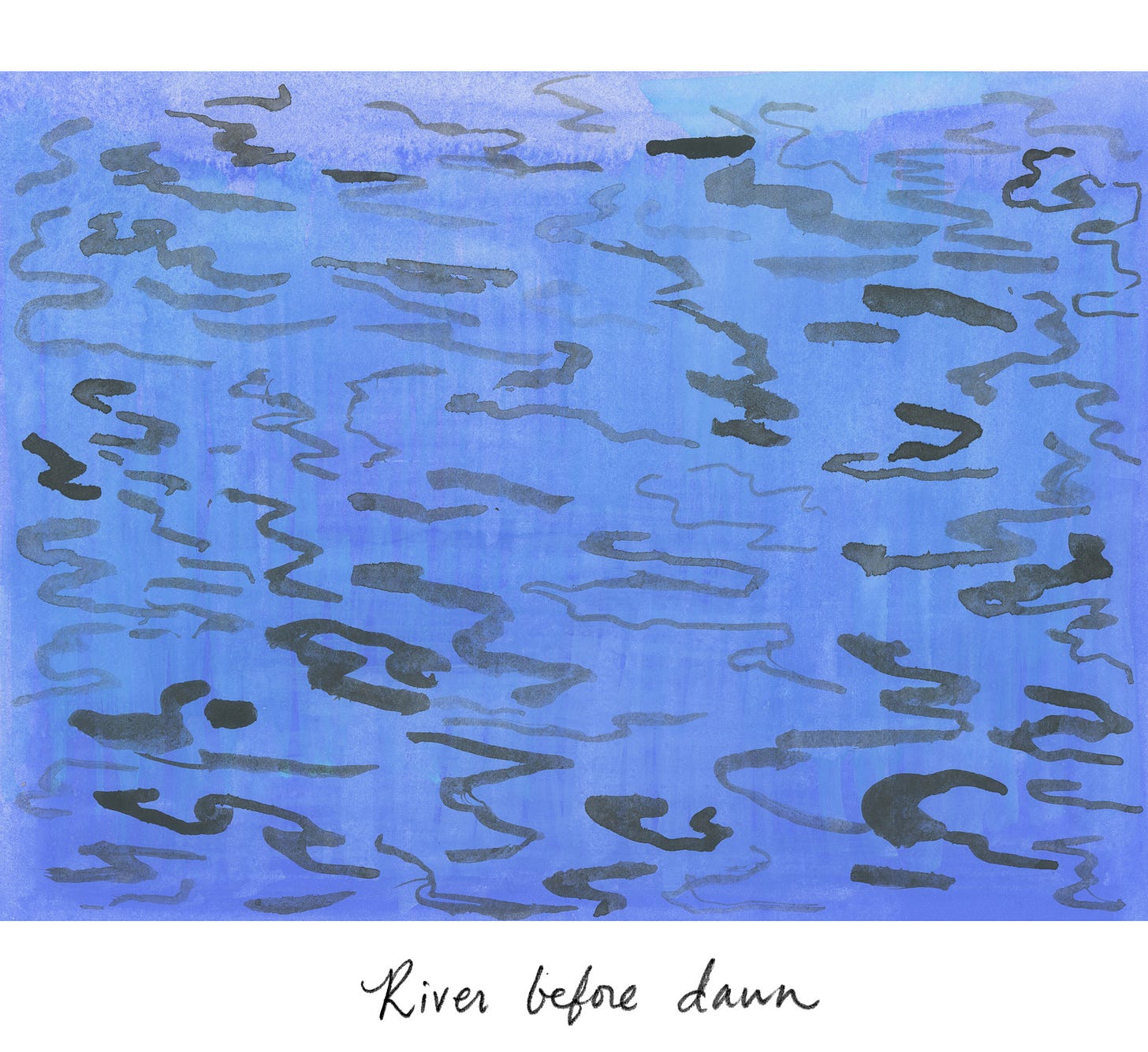

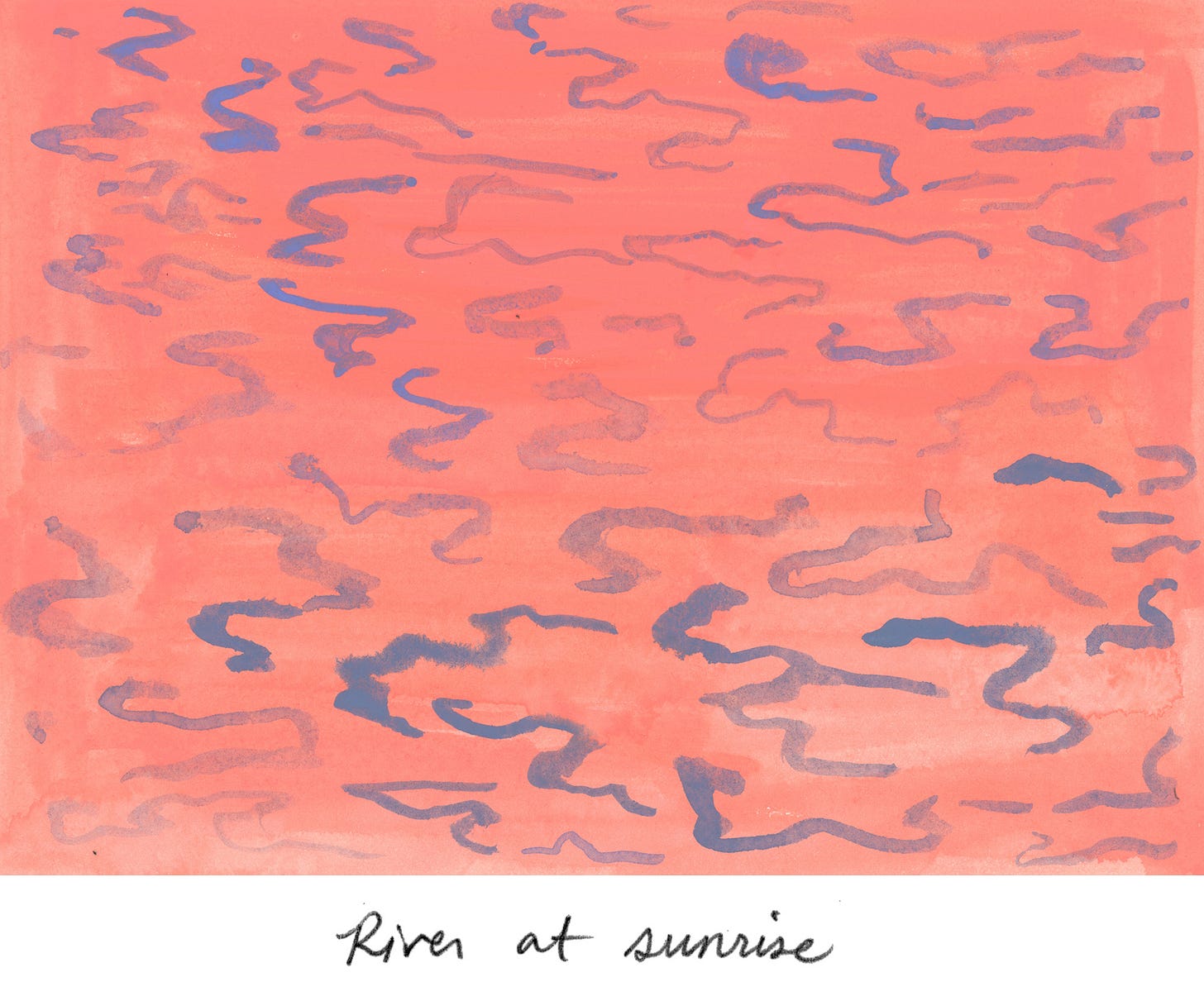

Hi, friends — there was a moment midsummer when things felt relatively “normal” (in my thoughts, in my dreams). That feeling has passed, as things do, and my anxieties are refueled anew. If you are in this boat with me, then let’s take a break and paddle down a reasonable river, where the swans appear out of the blue. —Amy Jean

There is usually a pair of mute swans (Cygnus olor) on the Housatonic river, where I like to row, paddling close to shore in shallow areas near reeds. They appear like mythical creatures out of the mist in early fall, when the water temperature is a few degrees warmer than the air.

Swans mate for life, though there are occasions of swan “divorce” when things don’t work out with nesting or other factors. They are one of the few bird species where males help with nest construction and incubation of eggs. They are also very protective of their nests.

When I’m rowing alone, I make a point of steering clear, though I have seen them “busking”—lifting their feathers into a fluffy display that makes them appear larger. (It is perhaps the most beautiful of warning systems.) Swan cygnets stay with their parents for about three months. Like other swans, they are known to grieve the death of birds close to them.

Mute swans are a complicated presence in North American waters. Originally from Europe and Asia, they were brought here in the late 19th century to inhabit ornamental ponds. Mute swans are voracious eaters and can be aggressive, changing the landscape of their territory, which they maintain over years. And so, there are reasons for management of mute swan numbers, depending on their location, though their population overall is low compared to other invasive species.

Mute swans are easy to observe over long periods of time, living to be around twenty years old. I find it hard not to appreciate this mega-fowl, which does not hide from human activity. My favorite experience is watching them in their awkward, remarkable run-up to flight.

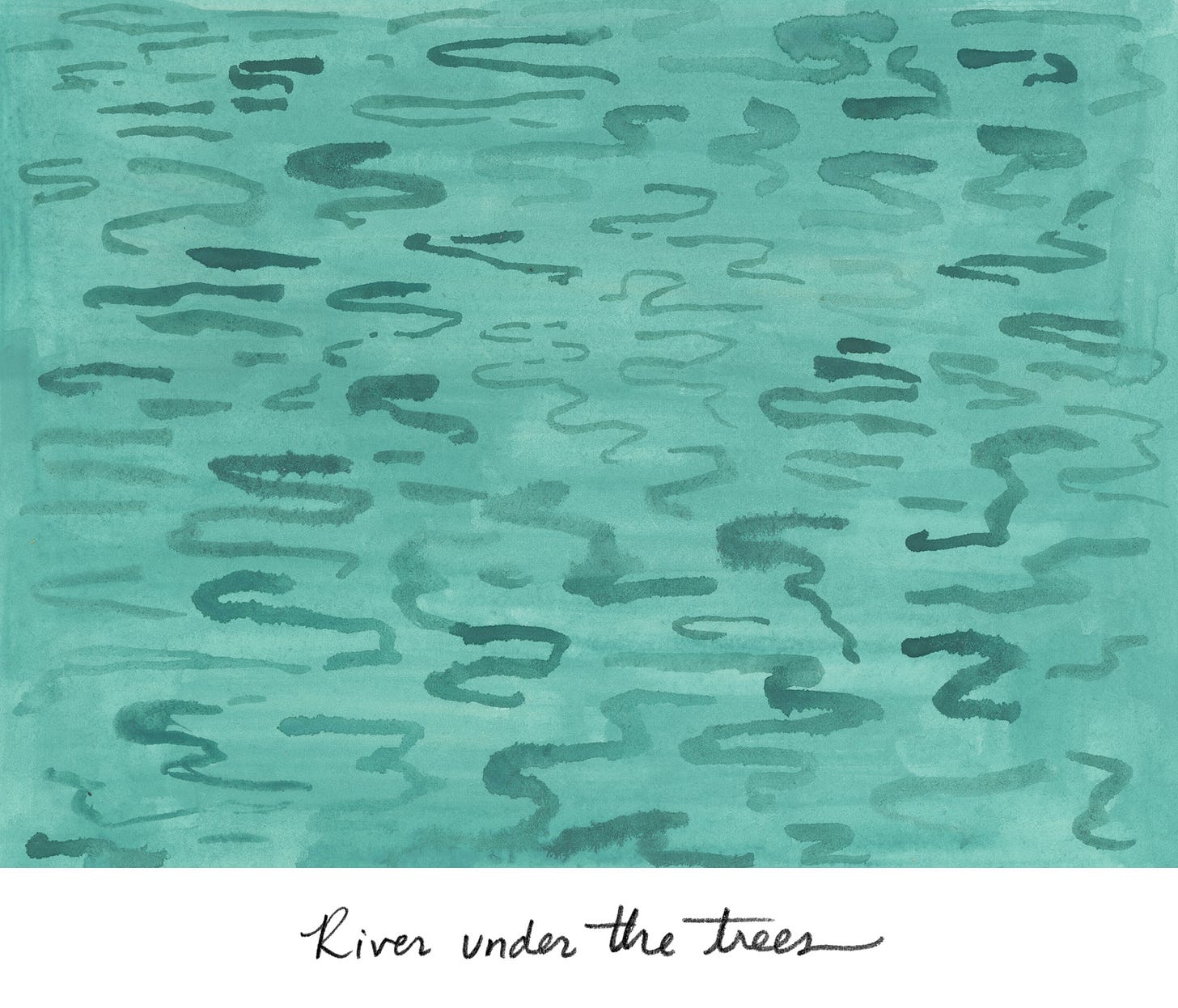

One morning in my small boat, I paused to watch a pair flapping and running on the water for yards, necks extended straight. Mute swans are one of the largest fliers, weighing up to 30 lbs, with wingspans of 8 feet. At the moment when their efforts seemed destined to fail, when flight felt impossible and doomed, the two birds lifted over the water and took off low along the tree line, following the river upstream, through the leafy-green light.

Mute swan links—

Some gentle footage from the UK of a mute swan pair in marshy water, not far from a road, taking care of their cygnets, feeding, busking, nesting, flapping [via YouTube]

Animal encounters in recent comments—

A ladybug at 11,752 feet elevation—thank you to Heather. And to Elizabeth for skimmers and dragonflies; both here.

Also—

Next time: the orb weavers are making their big webs.

Wild Life #30 / this newsletter is a place to learn about the life around us, one big wingspan at a time. If you enjoy reading, please share with a friend, colleague, neighbor, teacher. Have a great weekend, and see you in a couple of weeks.

I'm with you on the anxiety and stress struggles. I have been struggling to create at all! This is lovely.

Beautiful pictures Amy, thanks for sending them.